Hi Neil,

Thanks for the vote of confidence. We are working to make them better, never fear.

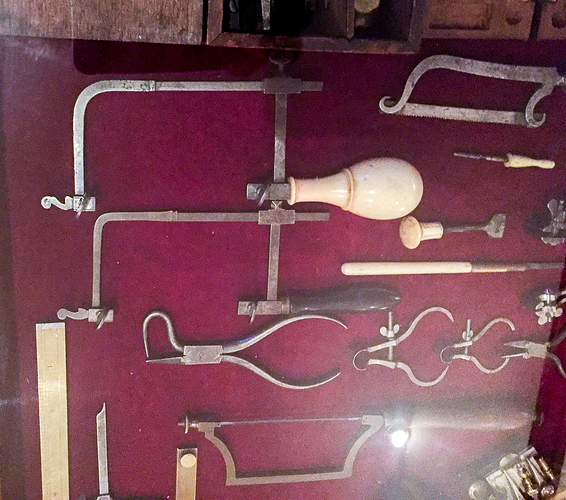

It took me a while to get permission to post the picture, but a friend of mine collects antique tools. He has a couple of fairly early jeweler’s saws in his collection, so I’m posting a quick cellphone shot, since it’s what I’ve got.

Quote:

“Not sure which ones were in there at the moment you were here but my guess is the one with the bulbous ivory handle is late 18th century, it shows up in catalogs circa 1770 's, the one with the thin ebony handle is signed Peter Stubs, circa 1810 to 1830. Both have the leaf spring finial to open the top blade clamp. This feature is very rare and not seen past second quarter of the 19 th century.”

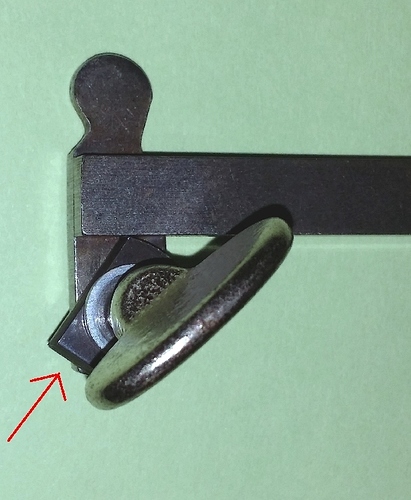

The interesting thing to note is that the little ‘stub’ on the traditional designs that we all use now to hook on our bench pins during tensioning, if we even notice it at all, was originally a split spring used to spring the two sides of the forward clamp apart. They were attached to each other, and not capable of getting out of alignment the way the modern version does. The original design didn’t (and couldn’t) have the problem that Neil hates. The other thing to notice is that the spine bows change section. They’re forged. Which means they’re real steel, properly heat treated, not just a bent bit of rectangle wire. Vastly stronger than the modern incarnations.

What you’ve got, in a modern version of the ‘traditional’ design is something that’s been like a game of telephone, getting fainter and fainter with every repetition, for more than 200 years. Every time somebody did their own version, they kept looking for ways to shave a penny out of it here and there, and it eventually got shaved down to the point where it was essentially worthless.

I saw the same thing in the design of coping saws, when I looked at those before designing ours. The very early ones weren’t bad. They were as good as they could be, given what they had to work with. Then the manufacturers got into a race to the bottom for price, and they cheapened the design without understanding what made it work. To the point where they now basically don’t.

I built a machine not long ago that lets us test the tension that a sawframe will put on a blade. The best (old) coping saw I can find puts 52 pounds of tension on a blade. The Stanley Fat Max (their ‘fancy’ version) I picked up at Home Despot last year does 32. And ours does 87+. Which matters. A lot.

Of course, we’re 10 times the price of that Stanley, but there are individual parts in ours that cost us more to make than that Stanley retails for. If you aim to compete with a $15 dollar retail, there’s a limit to what you can do.

In a certain way, I can understand, and have sympathy for the production decisions that led to some of the compromises in the modern saws. I look at the old hand-made, one-at-a-time designs, and there’s almost no way to do them like that in a production situation. You just can’t. So I can see the fight, one little detail at a time, one cheaper part here, one spring turned into a decorative doo-dad there, and I understand it. But at the end of the day, you end up with something that’s nothing like what it was originally.

It’s been an interesting and eye opening few years, working with Lee on the saws. Even coming from a background in production jewelry, doing the kind of volume production we’re doing now is a whole different world, and it forces you to think in completely different ways.

For example, we’ve been having trouble (now fixed) sourcing titanium for our Ti saws. The mills were producing Ti that was spec’d at .125" thick. But it was spec’d to ASTM (56something or other), which calls out for a thickness tolerance of plus/minus .010". And they were producing sheets at .1165". Just barely inside the sloppiest possible tolerance. Which doesn’t sound like much until you realize we’ve got parts already made that were designed to fit .125" plus/minus .005. (A sheet of paper, more-or-less) These things are twice the tolerance low, and would be noticeably sloppy if we used them. (we didn’t.) But you’ve got to keep an eye on the ‘traditional’ tolerances for each different material you use, and set up your design to deal with sloppy (or tight) stock over many different runs. Either that, or get used to calling out the spec you need, and inspecting the material to make sure. Not something that jewelers normally spend much time worrying about. If I buy gold at 1 mm thick, I can pretty well count on it being 1.00 thick, plus or minus nearly nothing. And there are both economies and costs to scale. Some of our parts for the saws we do in batches of 5000 at a pop, or more. Which does make them cheaper, in terms of setup, but it forces you to think of designs which can be produced in those kinds of numbers without making everybody totally insane. My hat’s off to Tim, our assembly guy, who puts hundreds of the saws together every week, without going completely nuts. I couldn’t do it. I have done it, and it makes me crazy. (I’m a good production designer and prototype machinist. Hundreds of the same part every week, for months? No. My head would explode.)

I’m not entirely sure where I’m going with this, except that I find the differences in the way you need to think about design for large scale production are radically different than the way jewelers think about production design, if they even think of it that way at all.

Another part of the world heard from, I guess.

Regards,

Brian Meek

Knew Concepts.